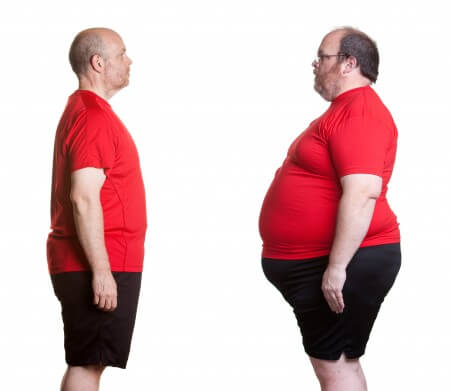

We once thought that weight loss was all about calories in, calories out, or just diet and exercise. Or perhaps, it’s in your genes or hormones like leptin. However, your gut bacteria might actually have more to do with your weight than you think. Read this post to learn about how probiotics could help you lose weight and improve your metabolism.

How May Probiotics help with Weight Loss?

1) Reducing Calorie Harvest from Foods

In mice and rats, obesity-related microbes can harvest more energy from food than the microbes that are found in lean animals [1].

Compared with lean mice with normal genes, the gut bacteria of obese mice have more genes that can burn carbohydrates for energy [2].

2) Changing Metabolism

How the gut bacteria metabolize primary bile acids to secondary bile acids affect our metabolism by activating the farnesoid X receptor, which controls fat in the liver and blood sugar balance [3].

Also, activation of bile acid receptors can increase metabolic rate in brown adipose tissues (fat that burns fat) [4, 5].

Intestinal microbiota can affect host fat storage [6].

In mice, diet accounts for 57% of changes in their gut microbiome [5].

3) Fecal Transplants

Gut bacteria from stools of healthy and lean humans transferred to obese people with type 2 diabetes increased insulin sensitivity and gut bacteria diversity in a clinical trial on 18 people . However, this study did not observe significant changes in body mass index 6 weeks after the transfer [7].

In a case study, fecal matter was transplanted from an overweight donor to a lean patient for C. difficile infection treatment. After the transplant, the recipient had increased appetite and rapid unintentional weight gain that could not be explained by the recovery from the C. difficile infection alone [8].

Feeding obese and insulin-resistant rats with antibiotics or transplanting them with fecal matters from healthy rats reversed both conditions [9].

In identical twin rats with discordant phenotypes (e.g., one obese and one lean, despite identical genetics), the gut bacteria also seems to control their metabolism. Germ-free mice (with no gut bacteria) populated with the obese twin had increased fat cells and reduced gut bacteria diversity compared to mice that were populated with the lean twin’s fecal matter [10].

In humans, more clinical studies would be necessary to determine whether fecal microbiota transplants can have long-term effects on insulin sensitivity or weight, even though fecal microbiota transplant improved the gut microbiome for up to 24 weeks in a small trial on 10 people [11].

Presently, there are several phases 2 and 3 clinical trials for fecal microbiota transplant [12].

While results thus far have shown that fecal microbiota transplant is a promising therapy for metabolic problems, it does come with risks, including [12]:

- Infections getting carried over with the stool transplant

- Side effects such as diarrhea or fever

- Negative traits or health problems could potentially be transferred along with the gut bacteria

4) Controlling Appetite and Satiety

Prebiotic fermentation by the gut bacteria may increase gut hormones that promote appetite and glucose responses (such as GLP-1 and peptide YY), as seen in a clinical trial on 10 healthy people and a study in rats [13, 14].

5) Reducing Inflammation from “Leaky Gut”

Weight gain is associated with “leaky gut” (intestinal permeability). This may increase circulating pro-inflammatory lipopolysaccharides in the bloodstream (endotoxemia) [15].

Metabolic endotoxemia can result in chronic, low-grade inflammation as well as increased oxidative damage associated with cardiovascular disease [16].

In mice with metabolic syndrome, treatment with a probiotic led to a significant reduction in tissue inflammation and “leaky gut” due to a high-fat diet (metabolic endotoxemia) [17].

Bacteroidetes vs Firmicutes – The Obese vs Lean Link?

Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla (groups) comprise ~90% of the human gut bacteria [18].

In one small study on 12 obese people, high Bacteroidetes levels correlated with weight loss [19].

A larger study in humans found that obesity was indeed associated with [2]:

- Reduced levels of Bacteroidetes

- Reduced bacteria density

- More bacteria genes that metabolize carbohydrates and fats for energy

Studies in mice and rats also confirmed the link between Bacteroidetes and leanness. Bacteroidetes are also more abundant in lean animals, while Firmicutes are more abundant in their obese counterparts [20, 21, 22].

However, in these studies, it was unclear whether the obesity-inducing high-fat diet caused the bacteria predominance or the bacteria caused the obesity.

Interestingly, mice that have 2 copies of the leptin gene also have a 50% reduction in Bacteroidetes, suggesting that obesity may also change the gut bacteria composition [23].

Note: Lactobacilli, Streptococci, and Staphylococci are Firmicutes, whereas Bifidobacteria are actinobacteria, which are neither Firmicutes nor Bacteroidetes.

Although a high number of Firmicutes (like Lactobacilli) in the gut seems to correlate with obesity, supplementation with Lactobacilli helped with weight loss in many cases.

Probiotic Strains for Weight Loss and Metabolic Health

Consuming probiotics can reduce body weight and BMI. A greater effect may be achieved in overweight subjects, when multiple species of probiotics are consumed in combination or when they are taken for more than 8 weeks [24].

Consult your doctor before taking probiotic bacteria. Never consume probiotics or implement any other lifestyle and dietary changes in place of what your doctor recommends or prescribes

Mixed Probiotic Blends

L. acidophilus, B. animalis ssp. lactis and L. casei reduced BMI, fat percentage, and leptin levels in a clinical trial on 75 overweight individuals [25].

Oral administration of B. longum, B. bifidum, B. infantis, and B. animalis decreased glucose levels, ameliorated insulin resistance, and reduced the expressions of inflammatory adipocytokines in obese mice [26].

In two clinical trials on almost 150 obese children, the intake of synbiotics (probiotics + prebiotics) resulted in a significant reduction in BMI, waist circumference, and some cardiometabolic risk factors, such as total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and triglycerides [27, 28].

Several studies have demonstrated that individual probiotic bacteria strains can help with weight loss. However, many of these are observational in nature, while others were done in animals.

Probiotic and Weight Loss

Bifidobacterium animalis

Humans with more B. animalis have lower BMI, while those with less of this bacteria have higher BMI [29, 30].

Daily ingestion of milk containing B. animalis ssp. lactis significantly reduced the BMI, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, and inflammatory markers in a clinical trial on 51 people with metabolic syndrome [31].

Bifidobacterium breve (B-3)

B. breve lowered fat mass and improved GGT and hs-CRP in 52 adults with obese tendencies [32].

B. breve reduced weight and belly fat in a dose-dependent manner. It also reduced total cholesterol, fasting glucose, and insulin in a mice model of diet-induced obesity [33].

Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 (BNR17 and SBT2055)

In 2 clinical trials on 272 overweight adults, these probiotic strains [34, 35]:

- Decreased body weight

- Reduced waist and hip circumference

- Reduced belly fat and fat under the skin

However, their constant consumption may be required to maintain this effect [35].

Both L. rhamnosus and L. gasseri significantly lowered weight in mice [36, 37, 38], while L. gasseri also reduced body weight in rats [39].

Lactobacillus paracasei

L paracasei decreased energy/food intake in a small trial on 21 people and a study in piglets [40].

Water extract of L. paracasei reduced body weight in obese rats. It decreased the formation of lipid plaques in the aorta, reduced fat cells size, and inhibited fat absorption, thereby reducing fat production (lipogenesis) [41].

Lactobacillus Plantarum (PL60 and PL62)

L. Plantarum PL60 and PL62 produce a fatty acid called conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), which can help increase fat burning in obese mice. After 8 weeks, L. rhamnosus PL60 reduced body weight and white fat tissues without reducing caloric intake [42, 43].

A low-calorie diet supplemented with L. plantarum reduced BMI in a small trial on 25 adults with obesity and high blood pressure [44].

Lactobacillus rhamnosus (CGMCC1.3724)

In a clinical trial on 125 obese adults, this probiotic strain [45]:

- Induced weight loss

- Reduced fat mass

- Reduced circulating leptin concentrations

Additionally, L. rhamnosus CGMCC1.3724 improved liver parameters in a small trial on 20 obese children with liver dysfunction noncompliant with lifestyle interventions [46].

Lactobacillus salivarius Ls-33

In a clinical trial on 50 obese adolescents, introducing L. salivarius Ls-33 increased certain groups of bacteria. Importantly, it raised the Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes ratio, associated with leanness [47].

Clostridium butyricum (CGMCC0313.1)

C. butyricum reduced fat accumulation in liver and blood, lowered insulin levels, and improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in obese mice. Furthermore, C. butyricum administration ameliorated GI and fat tissue inflammation [48].

Because this probiotic has only been tested in humans, there is no evidence that its weight-loss and antidiabetic effects will be the same in humans.

Probiotics Associated with Weight Gain

The following probiotics have been associated with weight gain in human and animal studies. You may want to avoid these if you are trying to lose weight [49]:

- Lactobacillus acidophilus – in both humans and animals

- Lactobacillus fermentum – in animals

- Lactobacillus ingluviei – in animals

- Lactobacillus reuteri – in humans, although it helps with some obesity-related symptoms [50].

Further Reading

For technical information, check individual probiotic posts:

- B. animalis (B. lactis)

- B. bifidum

- B. breve

- B. coagulans (L. sporogenes)

- B. longum

- B. subtilis

- C. butyricum

- L. acidophilus

- L. brevis

- L. casei

- L. crispatus

- L. delbrueckii (L. bulgaricus, L. lactis)

- L. fermentum

- L. gasseri

- L. helveticus

- L. johnsonii

- L. lactis

- L. paracasei

- L. plantarum

- L. reuteri

- L. rhamnosus

- L. salivarius

- P. freudenreichii

- S. boulardii

- S. cerevisiae

- S. thermophilus