The human body has an amazingly efficient detoxification system, mostly located in the liver. In healthy people, these detoxification processes are in balance, and most of the time function well. However, some diseases, vitamin deficiency, exposure to tobacco smoke, alcohol, and drugs may upset the balance between detoxification enzymes. This post will focus on phase I: the first step to removing toxins from the body. We’ve also compiled a list of natural factors that may increase or decrease the activity of CYPs, a big family of phase I enzymes.

Overview of Detoxification

Basic Mechanisms at Work

Modern life is based on the use of chemicals. The current count of individual substances is now approaching 100 million, and humans and other species are exposed to a great number of them [1].

Our bodies process and remove these foreign chemicals (xenobiotics) thanks to our efficient detoxification mechanisms. These mechanisms also deal with metabolic products such as excess hormones (endobiotics).

Xenobiotic metabolism usually converts fat-soluble compounds into more water-soluble derivatives that can be easily eliminated from the body [1].

“Enzymes of detoxification” are a big family of enzymes that participate in altering xenobiotics (i.e. foreign compounds), so as to make them either more readily excretable or less pharmacologically active [2].

Detox Phases

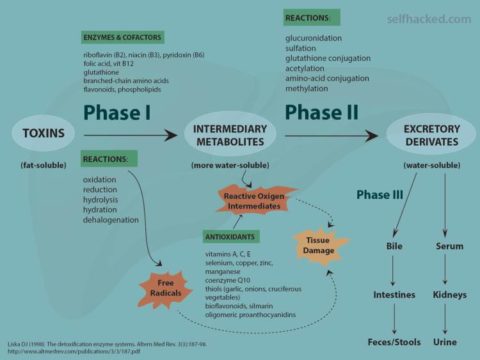

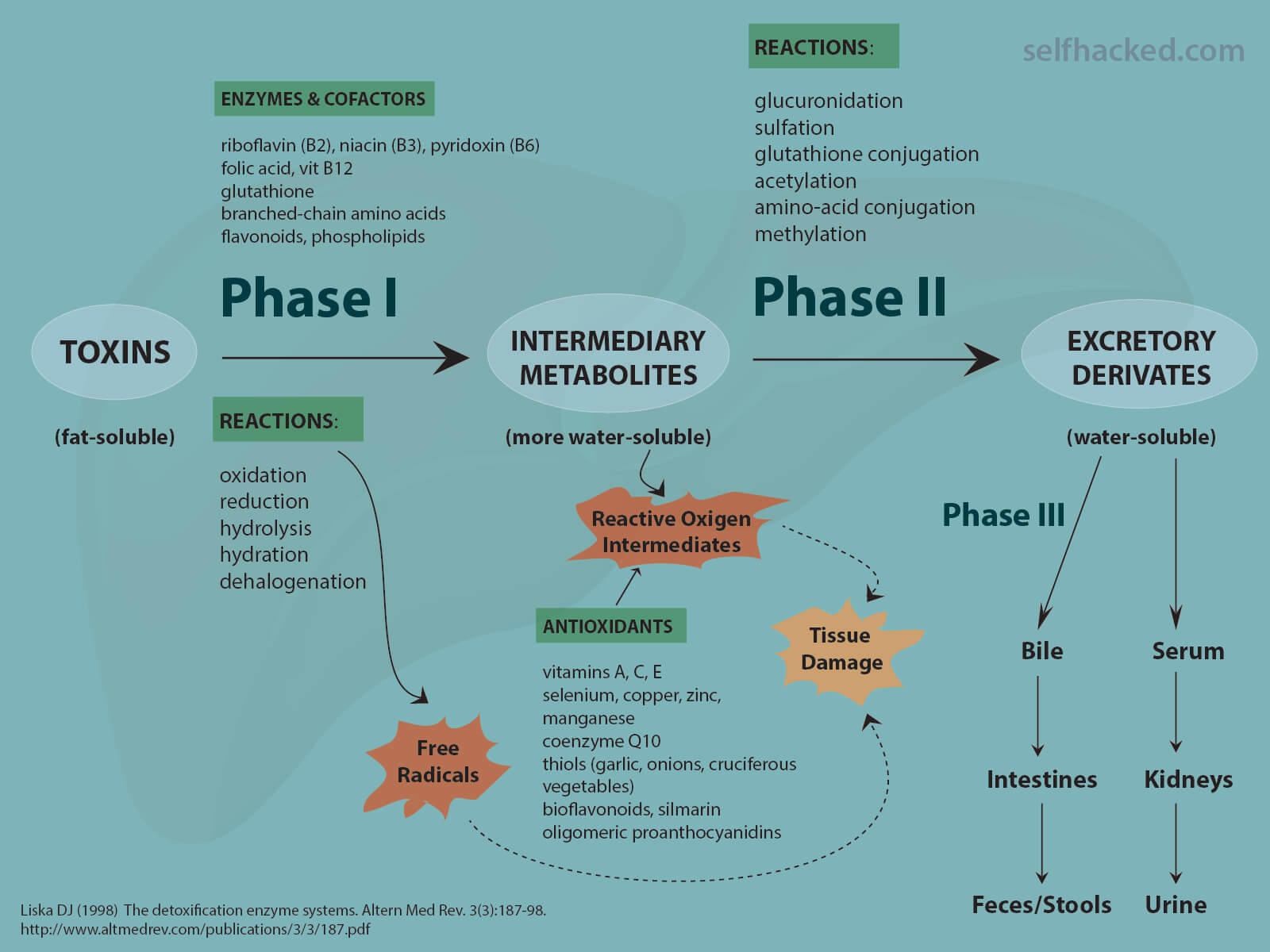

The detoxification process can be roughly divided into three phases [3]:

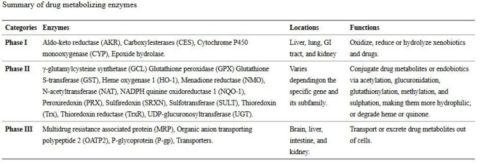

- Phase I is governed by transformation enzymes – these enzymes oxidize, reduce and hydrolyze toxins/drugs

- Phase II is managed by conjugation enzymes – these enzymes conjugate Phase I products

- Phase III is carried out by transport proteins – these proteins transport the final products from the cell

Phases I, II, and III must work in unison for the proper removal of unwanted toxins, drugs, and excess hormones.

These enzymes have broad substrate ranges. They are relatively more concentrated at major points of entry to either the body (liver, lung, intestinal mucosa) or a specific organ (the choroid plexus for the brain). Many also appear to be inducible, i.e. the body responds to exposure to a certain toxin by producing more of the enzyme that degrades it [2].

Detox Organs

The liver is the primary detoxification organ, as it filters blood coming directly from the intestines and prepares toxins for excretion from the body [1].

Significant amounts of detoxification also occur in the intestine, kidney, lungs, and brain, with phase I, II, and III reactions occurring throughout the rest of the body to a lesser degree [1].

The enzymes of detoxification are slow compared to other enzymes, but they are present in very large amounts. For example, Phase II glutathione transferases represent 10% of the total protein in the liver [2].

Phase I Detoxification: The First Step

Enzymatic Transformation Makes Toxins More Soluble

Phase I enzymes begin the detoxification process by chemically transforming fat-soluble compounds into water-soluble compounds. Water-soluble compounds can easily be excreted, while fat-soluble compounds can be stored in fat cells, where they are protected from the body’s detoxification enzymes [4].

Phase I reactions include oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis and cyclization [4].

These reactions are mediated by [1, 5, 6, 7, 8]:

- The versatile cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes

- The more selective flavin-containing monooxygenases (FMOs, responsible for the detoxification of nicotine from cigarette smoke)

- Monoamine oxidases (MAOs, which break down serotonin, dopamine, and epinephrine in neurons)

- Alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases (which metabolize alcohol)

- Epoxide hydrolases (EH), and

- Other phase I enzymes.

Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs)

Drug Metabolism & More

Through their unique oxidative chemistry, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs) catalyze the elimination of most drugs and toxins from the human body [9].

CYPs metabolize polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, aromatic amines, heterocyclic amines, pesticides, and herbicides, and the vast majority of other drugs [1].

However, CYPs also metabolize endogenous biochemicals (for example, CYP19A1, also called aromatase, transforms testosterone to estradiol) [10].

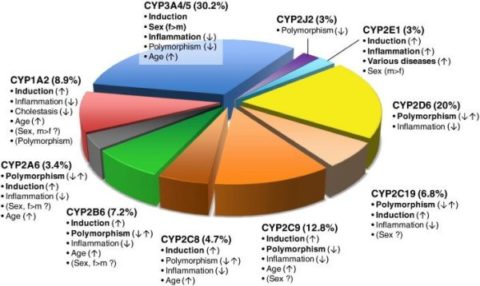

The Human Genome Project identified 57 human CYPs [4]. However, about 12 hepatic CYPs are responsible for the metabolism of the majority of drugs and other xenobiotics (approximately 93% of the drug metabolism) [1, 4].

Among them, CYP3A4, CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 are responsible for nearly 60% of the drug metabolism [4].

Note that although CYPs are detoxification enzymes, these reactions often convert less toxic molecules into more toxic active products. That is where the phase II detoxification steps in.

For example, CYP1A1 can activate some carcinogens [11, 12] while CYP2E1 can activate several liver toxins and contribute to alcoholic liver damage [13].

We differ in our CYPs

More than 2,000 mutations in CYP genes have been described, and certain single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been shown to have a large impact on CYP activity [4].

Genetic polymorphisms, which were shown to depend on ethnicity, play a major role in the function of CYPs (especially CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2B6, CYP3A5, and CYP2A6), and lead to distinct pharmacogenetic phenotypes termed as poor, intermediate, extensive, and ultrarapid metabolizers [14].

Polymorphisms in CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2C8, CYP2E1, CYP2J2, and CYP3A4 are generally less predictive, but data show that predictive variants exist [14].

Individuals in a population can be stratified according to metabolic ratios of particular CYPs. For example, the most frequent phenotype of CYP2D6 is extensive-metabolizer (78.8%). In other words, 78.8% of us are extensive metabolizers. This group is followed by intermediate- (12.1%), poor (7.6%) and ultra-rapid metabolizers (1.5%) [4].

Research suggests that, for example, a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer should not be administered codeine since the drug would have no effect. Conversely, a CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizer would likely suffer side effects from a normal dosage [4].

In one study, a polymorphism in CYP2C19, CYP2C192, was associated with a 30% increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events during treatment with clopidogrel. On the other hand, CYP2C1917 was linked with an increased risk of bleeding during clopidogrel therapy [4].

Nonetheless, more clinical research is needed before doctors can modify drug dosage based on each person’s CYP activity.

Factors that Influence CYPs (Sex, Age, Diet, Health)

The figure above shows the proportion of drugs metabolized by CYP enzymes. Important variability factors are indicated by bold type with possible directions of influence indicated by arrows. Factors of controversial significance are shown in parentheses [15].

Sex: Most clinical studies indicate that women metabolize drugs more quickly than men. This is particularly the case with the major drug-metabolizing CYP3A4. Analyses have shown ~2-fold higher levels of CYP3A4 protein in female compared to male liver tissue [15].

Age: Studies in the human liver suggest a modest increase in expression and activity of most CYPs during life, particularly CYP2C9 [15].

Disease: Evidence suggests that disease states generally have a negative effect on drug metabolism capacity. During infection, inflammation, and cancer, circulating proinflammatory cytokines – such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 – seem to lead to severe downregulation of many drug-metabolizing enzymes [15].

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have reduced cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme activity [16].

On the other hand, CYP2E1 is upregulated in diabetes and may contribute to the ongoing cellular damage observed in diabetes and obesity, according to some researchers [17].

Diet: According to limited research, protein deficiency inhibits, while protein-rich diet increases CYP activity [18]. A high-carbohydrate diet was shown to decrease CYP activity in one older study, but present-day studies would need to confirm this link [19].

On the other hand, a diet high in saturated fats was suggested to activate CYP2E1, the enzyme that was shown to be upregulated in diabetes [17].

What Lowers CYP Activity?

A Word of Caution

Altered (increased or decreased) CYP activity underlies most drug interactions.

It’s one of the reasons why supplement-drug interactions can be dangerous and, in rare cases, even life-threatening. Remember, CYP enzymes metabolize most drugs.

Theoretically, all substances that lower CYP activity may slow the metabolism of drugs and increase their blood levels. This may lead to an increased risk of toxicity or serious side effects.

On the other hand, substances that increase CYP activity may speed up the metabolism and removal of drugs. This can reduce the drug’s blood levels and make it less effective.

Always consult your doctor before supplementing or making any major changes to your diet or lifestyle. It’s important to let them know about all drugs and supplements you are using or considering.

Additionally, have in mind that detox supplements have not been approved by the FDA for medical use. Supplements generally lack solid clinical research. Regulations set manufacturing standards for them but don’t guarantee that they’re safe or effective. Speak with your doctor before supplementing.

Herbs, Foods, and Other Compounds

Many of the effects described below have only been studied in animals or cells. For nutrients lacking clinical data, CYP interactions in humans are unknown.

- Compounds found in grapefruit juice and some other fruit juices (including bergamottin, dihydroxybergamottin, and paradicin-A) have been found to inhibit CYP3A4, leading to increased bioavailability of CYP3A4-mediated drugs. These compounds thus increase the possibility of overdosing [20].

- Starfruit juice inhibits CYP2A6, CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, CYP2C8, CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 [21].

- Watercress inhibits CYP2E1, which may result in altered drug metabolism for individuals on certain medications (e.g., chlorzoxazone) [22].

- Goldenseal, with its two notable alkaloids berberine and hydrastine, has been shown to inhibit CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 [23, 24].

- Eurycoma longifolia, Labisia pumila, Echinacea purpurea, Andrographis paniculata, and Ginkgo biloba inhibit CYP2C8 [25].

- Propolis inhibits CYP1A2, CYP2E1, and CYP2C19 [26].

- Lycopene, a red pigment found in tomatoes, carrots, and watermelon, inhibits CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 [27].

- Licochalcone A, a major compound in traditional Chinese herbal licorice, significantly inhibits CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4 and exhibits weak inhibitory effects on CYP2E1 and CYP2D6 [28].

- Caffeic acid and quercetin, commonly found in plants, potently inhibit CYP1A2 and CYP2C9. Caffeic acid further inhibits CYP2D6 and weakly inhibits CYP2C19 and CYP3A4. Quercetin potently inhibits CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 and moderate inhibits CYP2D6 [29].

- Ginger extract inhibits CYP2C19 [30].

- Kale ingestion, unlike that of other cruciferous vegetables, may inhibit CYP3A4, CYP1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP2C19 [31].

- Piperine, a constituent of black pepper, decreases CYP3A4 [17].

- Oleuropein, derived from olive oil, inactivates CYP3A4 and slightly inhibits CYP1A2 [17].

- Garlic inhibits CYP2E1 [32].

- Resveratrol and garden cress inhibit CYP3A4 [32].

- Berries and their constituent ellagic acid may reduce CYP1A1 overactivity [32].

- Apiaceous vegetables may attenuate excessive CYP1A2 action [32].

- Chrysoeriol, present in rooibos tea and celery, may inhibit CYP1B1 [32].

- N-acetyl cysteine, ellagic acid, green tea, black tea, dandelion, chrysin, and medium chain triglycerides (MCTs) may downregulate CYP2E1 [32].

- Saint-John’s wort decreases CYP1A1, CYP1B1, and CYP2D6 [33].

What Increases CYP Activity?

Herbs and Foods

- Common valerian increased the activity of CYP3A4 and 2D6 [34].

- Ginkgo biloba increased the activity of CYP1A2 and CYP2D6 [34].

- Broccoli and cruciferous vegetables induce CYP1A1/1A2 [32].

- Resveratrol and resveratrol-containing foods enhance CYP1A1 [32].

- Curcumin may upregulate 3A4 activity [32].

- Rooibos tea, garlic, and fish oil appear to induce the activity of CYP3A, 3A1, and 3A2 [32].

- Saint-John’s wort can increase CYP3A4 [35, 36].

Toxins

- Tobacco smoke induces CYPs [37].

Hormones

- 17β-estradiol (E2) at high concentrations reached during pregnancy, increases CYP2B6 expression [38].

Note that many foods appear to act as both inducers and inhibitors of CYP enzymes, based on their concentration or composition (curcumin/turmeric, black tea/theaflavins, soybean) [32]. while other foods increase particular CYP enzymes while decreasing others.

It is also important to know that elevated Phase I activity is not always a good thing. As Phase I enzymes produce toxic and carcinogenic compounds, you want them to be in balance with Phase II enzymes.

Receptors that Activate CYP enzymes

The expression of phase I genes is governed by a number of nuclear receptors, including aryl hydrocarbon receptors (AhR), PPARα and orphan nuclear receptors such as constitutive androstane receptors (CAR) and pregnane X receptors (PXR) [3, 17].

These receptor interactions are highly experimental and proper human data are lacking:

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) activate Ahr, which in turn increases CYP1A and CYP1B enzymes [17]. This is an example where CYPs 1A and 1B oxidize PAH and aromatic amines to carcinogenic products [17].

- PXR binds small molecules such as steroids, rifampicin, and metyrapone, and increases CYP3A [17].

- CAR binds phenobarbital, orphenadrine and other drugs that activate CYP2B [17].

- Clofibrate and other chemical peroxisome proliferators activate PPARα, thereby inducing CYP4A [17].

Learn More

- The Science of Detoxification: How Phase II Affects Health

- The Science of Detoxification: Phase III & Detox Nutrients